Prior to the installation of the MLK exhibition on UNE’s Biddeford Campus in 2014, one would have been challenged to find many UNE students on campus who were even aware of the historic visit made in 1964 by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to UNE’s precursor institution, St. Francis College. St. Francis, despite occupying the very space on which UNE’s Biddeford Campus then sat (and still currently sits), likely seemed a relic of the past: an all-men’s Catholic college, run by Franciscan priests adorned in robes belted with rope cinctures, where students took classes in theology and were required to wear jackets and ties to class. It would hardly seem top of mind to 21st century UNE students to delve into the history and unique accomplishments of the little Franciscan college from which, in part, their great university sprang.

Fortunately, the MLK exhibit, erected in 2014 in honor of the 50th anniversary of King’s visit to campus brought a great deal of awareness of that historic day to the UNE Community. Located in present-day Leonard Hall, the very building in which King spoke, the exhibit is a prominent reminder of both the event and the movement of which it was a part to all those who pass by on a daily basis.

But how many among us at UNE today – students, faculty, professional staff, and administrators -- know the details surrounding King’s address at St. Francis? Under what circumstances did he take his one and only trip to Maine? What was it like on campus that May day in 1964 when King arrived? What did he do while visiting? What was the substance of his speech? And how did his presence and his words affect the students, the school, and the community?

While some of these questions cannot be answered in their entirety (no copy of King’s speech has been uncovered, and it was neither audio nor video recorded), we can ascertain a fair deal. From recorded interviews, captured in a 2001 film directed by Paul E. Clark ’01 with some of the organizers and attendees of the event, and an array of artifacts and newspaper clippings held in the St. Francis History Collection, we can piece together the panes of a window that let us peer back in time to this extraordinary episode in our institution’s past.

The year 1963 was a turbulent and tumultuous one in American history. On the civil rights front alone, among many other events, it saw the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, the slaying of civil rights activist Medgar Evers, the Stand in the Schoolhouse Door at the University of Alabama, and the March on Washington, let alone the assassination of President John F. Kennedy Jr.

That year, at St. Francis College, in Biddeford, Maine, quite far from the fray of sit-ins and firehose protests, a small group of faculty and students successfully organized and held an on-campus symposium on “The Christian in the Modern World.” An ambitious group, they no sooner completed the symposium than they turned their attention to the following year’s encore, and civil rights seemed the obvious and necessary theme. College administrators embraced the idea wholeheartedly, viewing it as very much in consonance with the mission of St. Francis and the Franciscan values of brotherhood, kindness to others, and assistance for the downtrodden. The late Father Donald Nicknair, O.F.M., dean of studies at St. Francis, who served as the chairman of the symposium committee, noted, “St. Francis cannot stand aloof, nor can it develop an indifference towards justice, let alone an outright flouting of Christian charity. Hence the purpose of our spring symposium:

to clarify issues in the minds of our students and parents, faculty, and total constituency by exposing them to public discussions, to organize the discussions on an intellectual plane by bringing together those minds that have toiled with the issues whether in religious, political, literary or sociological circles; to take a firm stand in favor of justice and Christian love toward everyone.”

As a college of liberal arts dedicated to the Christian values of life in the Franciscan tradition, St. Francis College sponsors this symposium on human rights, hoping thereby to make the Maine community more keenly aware of the fundamental problem that has marred our national social life for two centuries.”

— Father Clarence LaPlante, O.F.M., president of St. Francis College, 1963-1969

College President, the late Father Clarence LaPlante, O.F.M. (SFC ’53) believed a symposium on civil rights would serve an important role in bringing emphasis to the topic in Maine — where, due to the state’s homogeneity, the need for reform seemed less dire — while simultaneously upholding Franciscan beliefs. “As a college of liberal arts dedicated to the Christian values of life in the Franciscan tradition, St. Francis College sponsors this symposium on human rights, hoping thereby to make the Maine community more keenly aware of the fundamental problem that has marred our national social life for two centuries. We hope the discussions will engender light of mind and warmth of heart (Lucens et Ardens)” he said, invoking the college’s Latin motto, “so that those who participate may feel personally involved in so vital a human issue and strive to assure justice to all in a spirit of charity.”

So I was on the telephone waiting. And the next thing I heard was that voice that is memorable, that deep voice: ‘Hello, this is Dr. King,’ at which point, I think I was thunderstruck and speechless and probably hesitated. And he must have wondered whether the connection had gone.” — David DeTurk, humanities professor, St. Francis College

With the theme of the symposium set, committee members, including the late Professors Alfred Poulin (SFC ’60) and David DeTurk, could think of no one better to serve as a key speaker than the most influential leader in the civil rights movement, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who had recently delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech in August of 1963. So, despite knowing full well that their chances of securing him as a participant were infinitesimal, they forged ahead, called “information” to get the phone number of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which King headed, and then dialed the phone. Many years later, DeTurk remembered the incident vividly. “So I was on the telephone waiting. And the next thing I heard was that voice that is memorable, that deep voice: ‘Hello, this is Dr. King,’ at which point, I think I was thunderstruck and speechless and probably hesitated. And he must have wondered whether the connection had gone,” he recalled.

After regaining his composure, DeTurk proceeded to introduce himself and pose the question to King of whether he might consider speaking at the symposium. “I then explained to him what we were doing and what we were putting together. And, on behalf of the college and ourselves, asked him if he would be willing or interested in coming

up and participating in the symposium,” he recollected. “There was a pause on his end as he thought about that for a second. And he came back and said, ‘Yes, I would. I have never spoken in Maine.’ And so there we were. We made the arrangements and all that in maybe 20 minutes or so. It was a done deal much to our surprise.”

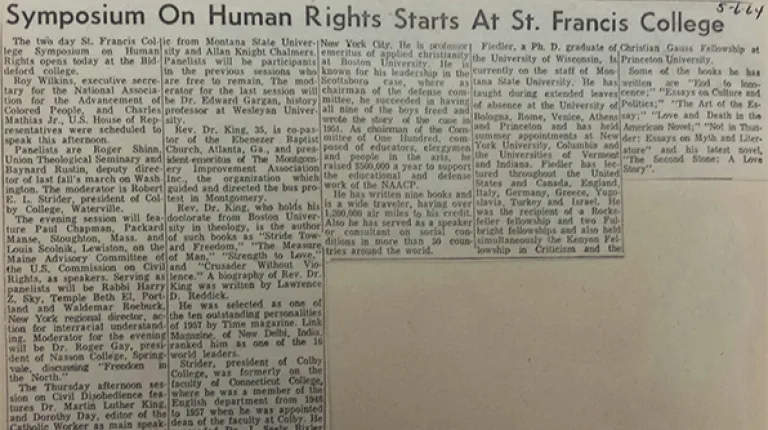

Flabbergasted committee members set to work organizing the details of the event. With King secured as the keynote speaker, they titled the event “I Have a Dream … The Negro and the American Quest for Identity: A Symposium on Human Rights.” The dates of May 6 and 7 were settled upon, and a number of potential national, regional, and local speakers were contacted and asked to participate. With such prominent names as Roy Wilkins of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People; Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic worker movement; and the controversial intellectual Leslie Fiedler, Ph.D., the impending event brought great excitement to campus and pronounced media attention to the college.

I remember that Newsweek, TIME, the big networks all covered it. It was in their magazines, and it brought a lot of people to the campus.”

— James Beaudry, St. Francis and UNE athletic director

With classes cancelled for the two-day period, St. Francis’ time to shine had arrived. “Our little campus here became the focus for a few days that was looked at by a lot of people,” stated St. Francis French Professor Robert Parenteau when reminiscing about the occasion some 37 years later. Longtime St. Francis and UNE coach and athletic director the late James Beaudry shared his recollections as well. “I remember that Newsweek, TIME, the big networks all covered it. It was in their magazines, and it brought a lot of people to the campus.”

I do remember when Martin Luther King pulled up to the front of Decary Hall. … I think there were 345 students and faculty, and they just gave Martin Luther King a big round of applause. And media was out there. And it was just a very special moment.” — James Pierce ’66, student symposium committee member and former UNE trustee

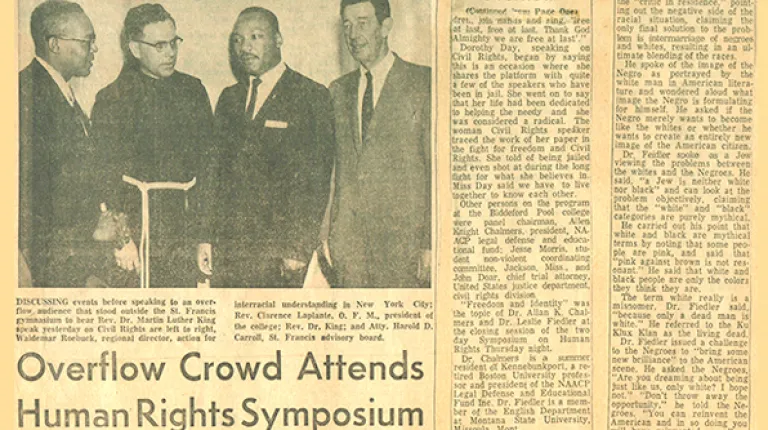

Just as enduring as any photographs snapped or articles written, the memories and emotional response of those who were in attendance stood the test of time. Student James L. Pierce, a member of the St. Francis Class of 1966, who served as a student symposium committee member, penned an op-ed in Florida’s News Leader in 2015, describing his impressions of King’s visit, as well as his unique experience of playing campus host to symposium panelist Waldemar Roebuck, the New York regional director of Action for Interracial Understanding, and chauffeur to a young Stokely Carmichael, who was tailing King at his speaking engagements throughout the country, recruiting members for Students for a Democratic Society. Among Pierce’s sharpest memories is the one of King’s arrival to campus. “I do remember when Martin Luther King pulled up to the front of Decary Hall. … I think there were 345 students and faculty, and they just gave Martin Luther King a big round of applause. And media was out there. And it was just a very special moment,” he reminisced.

LaPlante, as college president, had more intimate interactions with King and, a half-century later, recalled how the newly arrived visitor had expressed his wish to spend time in contemplative seclusion before embarking on the day’s activities. “When he arrived, he requested to be able to withdraw to a place where he would be quiet for some

time to recollect his thoughts. And I brought him to my room in Stella Maris, which is on the north side of the building on the second floor. And there, he sat in the window and just looked out and just remained pensive, thinking, mulling over, going over his thoughts,” LaPlante shared.

At noon, LaPlante collected King and took him on a tranquil walk along the perimeter of the Saco River estuary, pointing out various sea birds along the way, and eventually delivered him to the crowded cafeteria for his scheduled luncheon with conference goers, faculty, administrators, trustees, student symposium committee members, and other student leaders. LaPlante made introductions and requested that King offer a prayer. According to Pierce’s account, King stood up, said that he was “glad to take time off from the struggle in the South and come here among friends,” and proceeded to give thanks for being on the St. Francis campus and for being in Maine, before saying, “Let us pray.”

His voice. It was like, you just had to listen. He was very, very, very powerful.”

— Georgette Sutton, longtime St. Francis and UNE community member

At 2 p.m. on May 7, in the gymnasium, the “Civil Disobedience” segment of the symposium kicked off with Day’s address about the Catholic Worker publication, followed by a panel discussion. King then came to the podium. For some, like the late Georgette Sutton, longtime UNE employee and wife of the late St. Francis faculty member Bill Sutton, it was the sound of King’s voice that left a deep impression. “The gym was just packed,” Sutton remembered, setting the stage. “His voice. It was like, you just had to listen. He was very, very, very powerful.” The power emanating from King was something that Parenteau also recalled. “He seemed to be a very intense person, not only dedicated, but, you know, almost like, a missionary -- like on a mission.

He seemed to be a very intense person, not only dedicated, but, you know, almost like, a missionary -- like on a mission. There was something about him that took over his whole being.” — Robert Parenteau, French professor, St. Francis College

There was something about him that took over his whole being,” he noted.

But the power that King displayed, some attendees later remembered, was not the power of bombast. On the contrary, his power was rooted in his conviction and expressed with dignified poise and rhetoric. “He was very calm and obviously eloquent, as we all know, but in a very calm manner,” said DeTurk, “and he was not, in any sense of the word, a rabble rouser, as you would think in terms of someone who was screaming and hollering, and carrying on. No, no, no. Not at all. The rousing part of Martin Luther King, I think, was in what he stood for, what he exemplified, what he said, and what he believed.”

LaPlante had a similar impression. “When he did deliver his speech, it was very smooth and pleasant,” he recalled. “It was not fiery. It was not abrasive. It was mild and fluent; it flowed. It was eloquent at the same time and inspiring.”

He was not, in any sense of the word, a rabble rouser, as you would think in terms of someone who was screaming and hollering, and carrying on. No, no, no. Not at all. The rousing part of Martin Luther King, I think, was in what he stood for, what he exemplified, what he said, and what he believed.”

— David DeTurk, humanities professor, St. Francis College

As for the content of the speech, we know from media coverage that King began his portion of the symposium with the following statement: “The most potent weapon for the oppressed is nonviolent action in their battle for civil rights.” He briefly traced the country’s history of injustice to Black people, beginning with the slave trade and noted that despite progress, there was much more work ahead. “The Negro has a lot to do and a long way to go yet. The Negro has come a long way since the first Negro slaves were brought here from Africa,” he stated.

Segregation is on its death bed. It is still here, though, and it is hidden in the North. If democracy is to live, segregation must die.” — Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., St. Francis College “I Have a Dream” symposium

He expressed optimism that progress would, in fact, continue and articulated his belief that said progress would hinge on the quashing of the concept of racial segregation. “The Negroes have to suffer and sacrifice a lot to be free. Great strides have been made to extend the frontiers of civil rights. Conditions are better today than they were 25 or 30 years ago, and the walls of racial segregation will gradually crumble,” he said. “Segregation is on its death bed. It is still here, though, and it is hidden in the North. If democracy is to live, segregation must die.”

King referenced recent and specific examples of racial injustice, among them voter suppression, violence against Blacks, economic inequality, and the actions, taken less than a year earlier, of then Alabama Gov. George Wallace in defying both a federal court order and a presidential proclamation in his attempt to uphold segregation in schools. “We still see the Alabama governor peddling the ugly commodity of racial hatred. Negroes cannot register to vote in some areas, economic reprisals are taken against them, even outright death faces some of them,” he remarked.

We must get rid of the idea of superior and inferior races. There is no evidence of any race being superior, yet in spite of this, the idea still exists. Certain people even use the Bible to justify this idea.”

— Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., St. Francis College “I Have a Dream” symposium

While the end of injustice was contingent upon the end of segregation, the end of segregation was contingent upon the demise of belief in a racial pecking order, he argued. “We must get rid of the idea of superior and inferior races,” he pronounced. “There is no evidence of any race being superior, yet in spite of this, the idea still exists. Certain people even use the Bible to justify this idea.”

According to Parenteau, King emphasized that fair treatment should be the inherent right of all human beings for the very reason that they are, in fact, human. “He spoke about the moral dimension of social rights,” Parenteau said of King. “Social rights come from the fact of who we are. It's not

something that the state determines to grant as a privilege to somebody. It's something that we already have. We already have a claim to [it], by virtue of being humans, by virtue of being quite special in the world of all the creatures that there are — and of course, in a moral sense or a spiritual sense, the children of God. And, you know, you're a child of God, no matter what color you are, no matter what religion you have, no matter where you come from, and not only in this country but everywhere else in the world,” he summarized King’s point.

“He tried to emphasize the dignity of being human, to be a person — and vis-a-vis, the state,” Parenteau continued in his recollections of King’s address. “The state is not more important than the person. The state is at the service of the persons. The state is supposed to preserve the rights of the person. It's supposed to recognize them. It's supposed to pass laws that favor the respect of persons and helps persons who can't fend for themselves. But he was talking about people like you and I [but] who happen to be Black, who happen to be poor, who happened to be disenfranchised, who happen in many cases, to be uneducated, unable to fend for themselves, unable to organize by themselves. And they a needed a catalyst.”

The Negro must work hard to solve this problem. Non-violence through the courts and legislature are the methods to be used. More may have to suffer, be jailed, lose jobs, endure physical violence, even death, before we reach our goal.”

— Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., St. Francis College “I Have a Dream” symposium

If King was the catalyst to the civil rights movement, then non-violent civil disobedience was the reaction mechanism of choice. He underscored the importance of this means to an end in his symposium speech, suggesting that, while it would not be easy or expeditious, it was the only way. “The Negro must work hard to solve this problem. Non-violence through the courts and legislature are the methods to be used,” he advised. “More may have to suffer, be jailed, lose jobs, endure physical violence, even death, before we reach our goal.”

While symposium attendees could not, decades later, directly quote most of what King uttered that day, what stayed with them was the feelings inside of them that he had stirred. “When you’re 18, 19, 20 years old, that kind of participation, I think, forges your feelings and your outlook and, perhaps, your way of life,” Pierce said insightfully

in 2001. “I’m sure it changed an awful lot of folks who were here on campus at the time.”

The entire symposium experience, said DeTurk, helped shape attendees’ perspectives on the issue of civil rights, which was especially important in an all-white, all-Christian men’s college in northern New England. “I think most people got … a different feeling about the whole movement, not just from Dr. King, but from the others who came and spoke and visited with us,” he mused. “And I think it was a good thing because, at that time, I believe there had been very little active onsite involvement in Maine. It was still a little early for it to have reached us in Maine with any great impact.”

Thus, as we retract our gaze from the window into our past and refocus our vision on what is before us, we do so with a reminder of the power of conviction and of people working together to realize a shared vision.

Whether it be the passage of the Civil Right Act or the ability of a tiny Franciscan college in Maine to attract one of the world’s most prominent leaders, the notion that the firm belief in what is right and the willingness of people to work collectively on behalf of that belief can, in fact, turn what once seemed an impossibility into a reality.

If Leonard Hall is not on your usual walking route this week, make a point of stopping by. If you frequent the building, be sure to pause to look at the exhibit.

What you’ll see is a timeline of the civil rights movement and numerous images of and quotes about King’s visit to St. Francis. What you’ll know is that the visit was made possible by small group of ambitious college students, their dedicated professors, and a deeply caring administration. And what you’ll feel is twofold: reverence for a great man of deep conviction, who, while accustomed to addressing crowds by the thousands, made a journey to Biddeford, Maine, to say a prayer over a cafeteria lunch and to share his beliefs in a cramped school gymnasium … and, perhaps more surprisingly, a new respect for those who roamed the halls, rambled the campus paths, and dreamed at Jordan’s Point before you — robes, ropes, jackets, ties, and all.