Students become integral part of American chestnut tree restoration project

The University of New England prides itself on providing real-life, hands-on learning experiences for students. A project aimed at restoring the American chestnut tree is a prime example of that.

“So many people in my generation want to do something to help the environment because we keep hearing that the planet is dying, the planet is dying,” stated Virginia May (Environmental Science, ’24). “It is our responsibility to take collective action, and collective action is doing research like this. The fact that we can bring back even a part of the natural biodiversity of New England is incredible.”

Once touted as “the redwood of the East,” the American chestnut was all but destroyed during the last century by an accidentally imported fungal blight that is still killing the few remaining trees today. The blight has wiped out an estimated four billion chestnuts.

A few years ago, Tom Klak, Ph.D., professor in the Department of Environmental Studies, embarked on a mission to foster the comeback of the American chestnut tree. Now, his students are an integral part of the project.

“It has been incredibly fulfilling,” May said. “One of the reasons that I really wanted to come to UNE was because I knew there was a lot of undergrad research being done. This is an amazing project, and I really wanted to be in on it.”

Before this past summer, Kate Ganley (Environmental Science, ’24) did not know much about the American chestnut tree.

“I did some research on my own to gather the history of it, and I had never even realized that the American chestnut was such a keystone species in our ecosystem on the East Coast,” she explained.

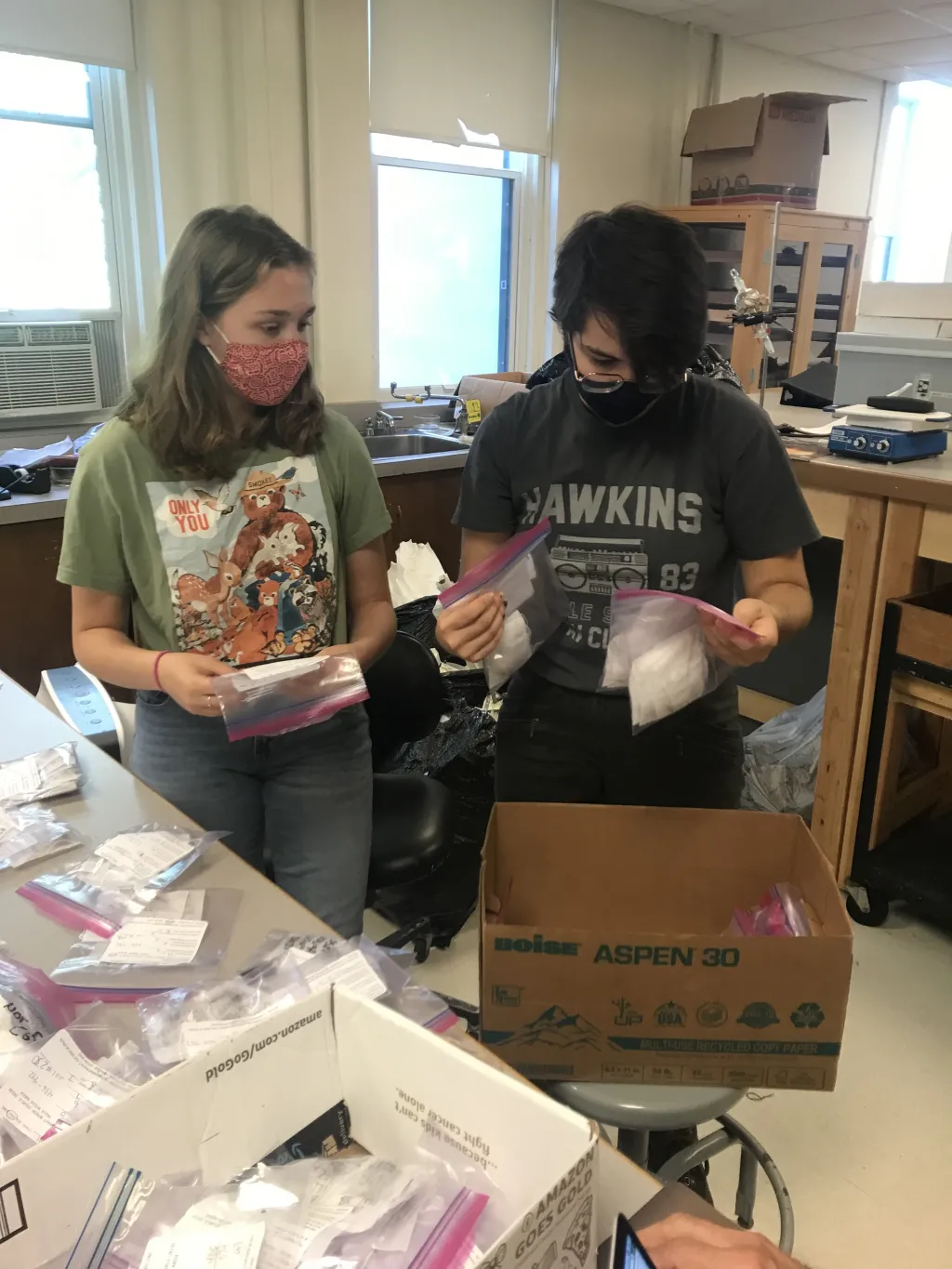

We recently caught up with Ganley, May, and two other students in Klak’s lab where they were shucking burrs and removing their transgenically-pollinated chestnuts, then recording the data on them.

“It is definitely a very different experience than what you would consider a normal type of classroom setting,” Ganley commented. “We do not work out of a textbook; instead we work as an interactive team and less of a class. Today we are labeling all of our chestnuts and processing that data to analyze later. A few weeks ago, we were out in Cape Elizabeth harvesting the chestnuts and monitoring our blight-tolerant seedlings.”

Klak collaborates with a team of scientists who created the fungal blight-tolerant chestnut seedlings by inserting a gene from wheat into them. The wheat gene protects the plant from fungal blight. UNE is the only place in New England and one of the few places in the country that has the seedlings. Through intense, speed breeding conditions in the greenhouse and lab at the Harold Alfond Center for Health Sciences, Klak and his students got the seedlings to produce pollen in about a third of the time they would typically take to produce it outdoors. The pollen was then put on the female flowers of American chestnut trees in Cape Elizabeth.

So far, the experiment appears to be working because the pollen has helped those trees produce fertile chestnuts. Those chestnuts now contain all of the genes of the wild trees being killed by the fungal blight and the blight tolerant wheat gene.

“We will grow those chestnuts up as big as we can in the UNE greenhouse, and then we'll plant them out in the field,” Klak said. “Based on all the science we know so far, we think that the ones that have the wheat gene will be protected. So, this is our New England field experiment to see whether we got our lab science right.”

Klak is excited seeing his students so energized by this project.

“It is an exhilarating thing to be able to make a difference in the world in terms of the environmental impacts,” Klak stated. “We sometimes feel overwhelmed, but here is a project where we can literally feel day by day that we are moving in the right direction to turn around some of the ecological damage that's been happening.”

He recently told the Bangor Daily News that if the experiment helps restore the mighty chestnut to American forests, it would be “the biggest ecological turnaround in North American history.”

The students are hoping the project will become a legacy that they can leave behind for future generations. It is definitely a project they will continue to follow no matter what paths their lives may take.

“I will always want to follow what is happening with the American chestnut tree because now that I know it's a keystone species, I think it is important that we keep tabs on such a key member of our ecosystem,” Ganley said.