The funding will support the development of a sustainable "living shoreline" along a waterfront stretch of campus

The University of New England will use nearly $140,000 in grant funding to mitigate coastal erosion and restore parts of the shoreline on its Biddeford Campus that researchers say have been marred by the effects of climate change.

UNE has been awarded a two-year, $138,432 grant from the Builders Initiative and the Broad Reach Fund, through the Maine Community Foundation, for the development of a living shoreline on its campus along a portion of Saco River, where researchers say they have seen the degradation of salt marshes that is likely the result of sea level rise and increased flooding events.

Living, or “green,” shorelines use plants or other natural elements to stabilize endangered coastlines and, over time, restore endangered coastal ecosystems. Such solutions are preferred over harder, “gray” shoreline structures like bulkheads and rock revetments, which decrease shoreline biodiversity and can actually contribute to erosion of the sea floor.

Pam Morgan, Ph.D., professor of environmental studies at UNE, who is leading the project along with Alan Thibeault, vice president for University Operations, said a living shoreline will help shield UNE’s campus from coastal erosion while protecting the plants and animals that students routinely use to conduct research.

Morgan said the grant will initially fund the design and permitting of the shoreline, which she noted is intended to be a model project that others can simulate in the shared effort to combat climate change.

Pam Morgan, Ph.D.

“We want this to be a place where people can come to learn more about nature-based solutions to the issues presented by our changing climate,” she said. “We also envision this as a perfect way to engage young people in conservation and restoration work that they will take with them in the future.”

The strip of coastline UNE hopes to restore, a horseshoe-shaped inlet in front of the Danielle N. Ripich Commons, faces the Saco River and sits on the Gulf of Maine, which — according to scientists at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute — is warming faster than 97% of the world’s ocean surface.

Such warming is driving flooding and erosion—the likes of which have never before been seen in Maine — such as December’s historic wind and rain storm, which flooded entire towns, fissured roads, and downed power lines across the state.

Our students crave opportunities to take positive action in the face of climate change … [t]he Living Shoreline Project is giving them the chance to be part of a solution, and that feels good.” — Pam Morgan

Morgan and her students have spent years surveying the area for signs of decline, and they have documented erosion in the salt marshes and riverbanks.

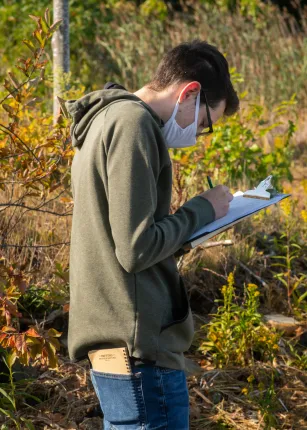

Students have helped lay the groundwork for the living shoreline project by conducting bank instability assessments, evaluating the salt marsh structure and function, assessing the marshes’ vulnerability to erosion, and identifying the flora and fauna of the area. They have also met with professionals who have experience in living shoreline projects and created mockups of the design as part of their efforts to mitigate further decline.

The shoreline in 1943.

The shoreline in 2023.

“Our students crave opportunities to take positive action in the face of climate change, especially when so much of what they hear these days is doom and gloom about the future,” Morgan stated. “The Living Shoreline Project is giving them the chance to be part of a solution, and that feels good.”

Similar projects have been piloted in Maine — notably in Freeport, Brunswick, and Yarmouth — but there are still no accepted best practices for construction. Such projects make use of geosynthetic baskets filled with oyster shells as well as fallen trees, which are intended to reduce the impact of waves on the shoreline.

UNE plans to take a similar approach in constructing its living shoreline, Morgan said, adding that restoring the coastal marsh will have the additional benefit of helping to remove carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas, from the atmosphere.

Students survey the shoreline and inspect for signs of coastal erosion at the site in 2020.

“The Living Shoreline Project is a win-win for students, the University, and the wider community of people affected by the erosion we are seeing along Maine’s coast and rivers,” she remarked.

Andrea Perry, program director for the Broad Reach Fund, said the model component was a key factor in awarding the grant funding.

“Our climate-related funding prioritizes projects that can demonstrate a component of mitigation or adaptation to climate change that others can learn from,” she said.