Masters of the Deep

Story by Joel Soloway

For as long as they can remember, UNE’s current cohort of Marine Science graduate students have always felt compelled to work in and around the world’s oceans. Just as it is impossible to restrain the sea, it is unthinkable for these students to hold back their passion for studying the marine sciences.

Abigail Hayne (’23), a former UNE undergraduate who returned to campus last summer to pursue her master’s degree, is a self-proclaimed “steward of the ocean” and strives to protect, conserve, and manage it. For her to be successful, ongoing research must continue to help us understand the complexities of this vast and varied ecosystem. “The ocean is like another world,” Hayne says. “Even though it’s on our planet, there is just so much we still don’t know.”

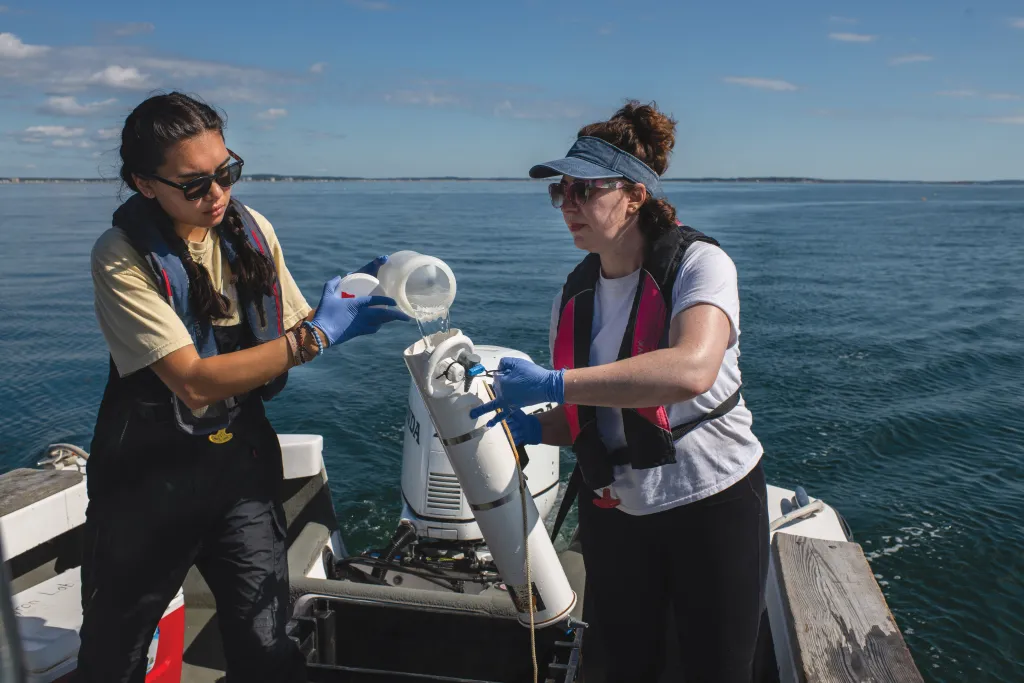

The relatively small Marine Science Master’s program at UNE typically has about a dozen students enrolled each academic year. Despite its modest size, all graduate students participate in research projects that expand well beyond the classroom walls and dive deeper into various aspects of the marine biosphere.

Hayne and classmate Addie Binstock (’23) study sharks. Under the guidance of Marine Science Professor John A. Mohan, the students are investigating topics related to the elemental chemistry of shark vertebrae and the post-release mortality rate found in four commonly caught shark species. Other studies within Mohan’s lab include the research that Alexa Cacacie (’23) is conducting with striped bass in the Saco River and a study by Ben LeFreniere (’23) on the ecology of white hake in the Gulf of Maine.

LaFreniere, one of three current master’s students completing the 4+1 track, jumped straight into the graduate program and research with white hake after receiving his bachelor’s degree this past May. “Even though white hake are very prevalent here in the Gulf of Maine, there hasn’t been a lot of research on them, and there is a need. So I thought it would be cool to be one of the first researchers to take it on,” he says.

Beyond studies involving sharks and hake, UNE marine science graduate students are involved in a wide range of scientific endeavors. These include students researching the dietary effects and thermal tolerance of the American lobster with Professor of Marine Sciences Markus Frederich; understanding the diet and stress levels of grey seals through Associate Professor (and chair of the Biological and Marine Sciences Graduate Program Committee) Katherine Ono’s mentorship; and studying kelp farms, seaweed, and snail population interactions in the Gulf of Maine, via Associate Professor Carrie Byron’s lab.

An empowering aspect of UNE’s Marine Science Master’s program is the close relationship that students and faculty advisors have with one another. For Cara Blaine (’23), her connection with female faculty members and peers has been paramount. “There are so many amazing women here, and we have a lot of female role models in this department,” she explains. “I think that’s uncommon for a science program.”

Students and faculty agree that, for a while, the marine field appeared a certain way and only involved specific people — namely, White men. Just as more women are starting to enter the profession, people from other diverse backgrounds are too. “We’re starting to see the inclusion of more voices that haven’t always been heard in this space,” Binstock says, while discussing this topic with her classmates. “With a greater representation of perspectives, opinions, and ideas, our generation is going to be put in a position that’s better equipped to take on the challenges we face as marine scientists.”

There is no denying the current challenges that marine scientists face. Whether it is pushback from policymakers or the ongoing threats of global warming and climate change, there is constant pressure on leading experts to find solutions. Students at UNE are preparing to take on this responsibility. As Aubrey Jane (’23) puts it, “All of our research ties into the idea of being leaders of adaptability.” Instead of heeding the frequent and often impossible expectations for immediate solutions, these budding marine scientists explain that their focus is on helping to guide the world along the more realistic path of resiliency.

Jane provides an example of how some industries will likely need to adapt to expected changes on the working waterfront. “The current lobster boom in Maine is projected to eventually slow down as a result of the species’ climate-driven migration,” she says. “However, growing mussels or other bivalves as an alternative protein source from oceans could provide supplemental income for workers.” Similarly, Jessica Vorse (’22)* hopes her research on the food safety of edible kelp might also provide a sustainable alternative for people to obtain food.

Through coursework, research, and fieldwork, these students are learning how to be passionate advocates as well as scientific experts. Emilly Schutt (’22)* explains how she often gets frustrated when companies disregard expert advice and make choices that harm the marine environment. “I want individuals to support research taking place within their community,” she states. “Supporting the recommendations made by marine researchers will help waterfront communities

grow sustainability.”

Taylor Gibson (’23) agrees and takes pride in all the work she and her peers are completing while pursuing their master’s degrees at UNE. It is something Gibson knows will have a profound impact on the future of marine science. “The skills we’ve learned here will not only guide us further along in our professional careers but also advance pathways for those who come after us.”

*Because the program runs through the summer academic session, Jessica and Emilly were scheduled to graduate at the end of the summer (2022) and were still active students when this piece was being written and edited.

Bonus Content: Explore Four of UNE’s Marine Science Labs

Byron Lab

The Byron Lab seeks to understand how environmental factors and food web interactions could promote sustainable food production in our coastal ocean. Carrie Byron, Ph.D., and her student researchers examine questions related to food web structure and stability. The team works closely with shellfish and kelp farmers in Maine.

With her research grounded in marine ecology, Byron works as an associate professor in UNE’s School of Environmental and Marine Programs.

Frederich Lab

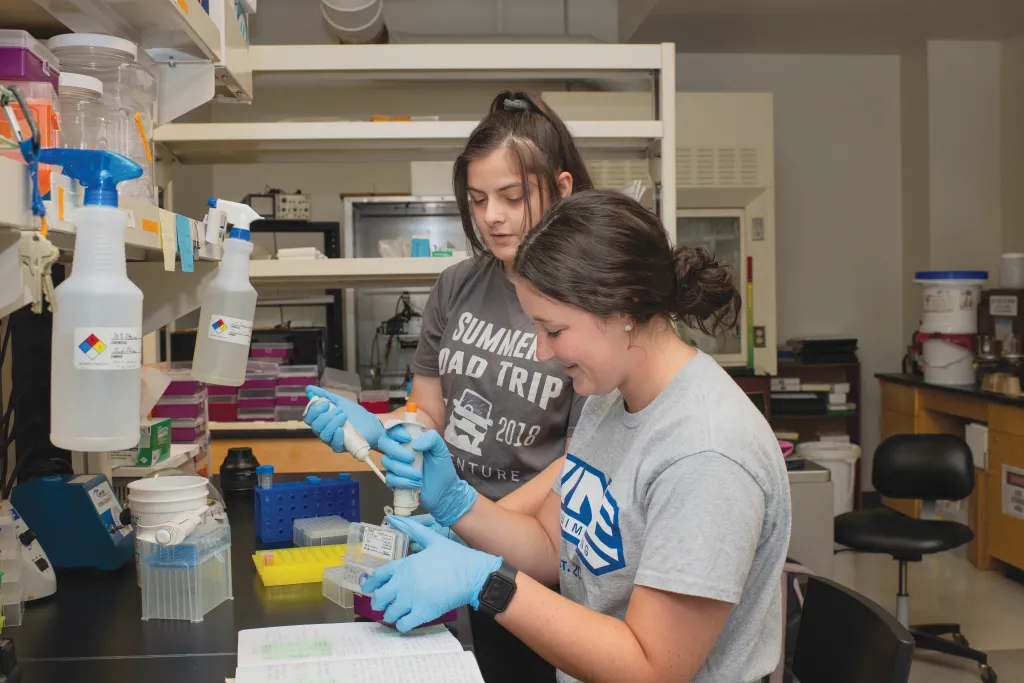

Housed in UNE’s Marine Science Center, the Frederich Lab investigates crustacean physiology, invertebrate biology, and marine invasive species. The lab’s current focus is on the European green crab and the American lobster. Marcus Frederich, Ph.D., and his team look to obtain an integrative understanding of how these organisms function in their environment. Student researchers use systems physiology as well as cellular and molecular methods to collect data and complete analysis.

Frederich has been a professor of marine sciences at UNE since 2003.

Mohan Lab

The Mohan Lab, otherwise known as UNE’s Shark and Fish Ecology lab, investigates links between fish migration patterns, habitat use, and trophic (i.e., food chain) interactions. The lab quantifies how environmental variation and anthropogenic stressors, such as recreational catch-and-release fishing, influence population health. Under the guidance of John A. Mohan, Ph.D., student researchers study a variety of species including sharks, striped bass, sturgeon, hake, stingrays, and more.

Mohan is the lab’s primary investigator and teaches at UNE as an assistant professor of marine sciences.

Ono Lab

The Ono Lab studies the behavior of grey and harbor seals in Maine. Kathryn Ono and her students monitor the diet of seals through DNA analysis of their intestinal contents. Beyond Maine, the lab also investigates the stress levels in grey seals off the coast of Cape Cod as well as captive seals from the National Zoo in D.C. Studies on the diving behavior of harbor seal pups have also been conducted.

Ono is an associate professor at UNE and serves as a chair for the Biological and Marine Sciences Graduate Program Committee.