Working to Transform Patient Screening and Treatment

by Emme Demmendaal

Imagine a world where a simple, routine blood test could detect cancer in its earliest, most treatable stages.

For people with some of the most aggressive forms of cancer, it’s a promising reality that Srinidi (Sri) Mohan, Ph.D., professor at the University of New England School of Pharmacy, has been working tirelessly to bring to fruition — one that has life-saving implications for underserved, rural communities across the globe.

Cancer research indicates that more than 9 in 10 women with breast cancer survive for five or more years when diagnosed at the earliest stage, but this survival rate plummets to just 3 in 10 when the cancer is caught in more advanced stages.

Treatment methods for breast cancer, especially for aggressive forms like triple-negative breast cancer, are limited by the inability to quickly determine treatment effectiveness and the lack of targeted therapies, often relying on toxic and expensive chemotherapy regimens that may continue even when ineffective.

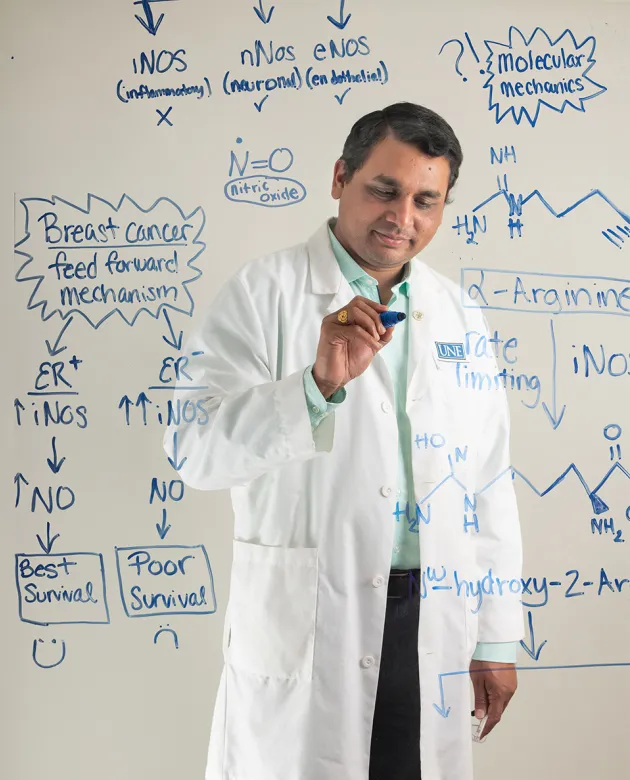

It’s an issue that Mohan ascribes to previous studies looking at the downstream production of nitric oxide, a signaling molecule that controls cancer cell growth.

From his previous research, Mohan discovered that a biomarker called Nw-hydroxy-L-Arginine, or NOHA, was both a sensitive and reliable indicator for estrogen receptor-negative tumors, a more aggressive type of breast cancer.

Existing research showed a connection between nitric oxide, inflammatory biology, and cancer, particularly breast cancer, he said.

That was when it clicked.

“The true ‘ah ha’ moment was when all dots connected and converged to this biomarker,” said Mohan, who is chair of the UNE Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Administration.

NOHA checked all the boxes. It was upstream of the nitric oxide process, could be measured with a blood test rather than a tissue sample, and correlated directly with nitric oxide levels without interference from other pathways, Mohan said.

He launched into investigating NOHA as a potential biomarker for breast cancer detection and monitoring, applying for a patent on a diagnostic tool for using this blood marker to detect aggressive, estrogen-negative tumors and track cancer growth.

The Power of Collaboration

While Mohan was making headway in a UNE lab in Portland, across the city, Susan Miesfeldt, M.D., a medical oncology clinician at the MaineHealth Cancer Care Network, was returning from a volunteer trip to Tanzania, disheartened by a significant lack of breast cancer management resources there.

Miesfeldt discussed the inability to easily determine a patient’s estrogen receptor status with another MaineHealth associate. Serendipitously, this colleague had recently attended a talk by Mohan, who discussed the potential application of a blood test for cancer screening and management.

“Sri had discovered this potential biomarker in his lab, and I identified this clinical problem halfway around the world,” Miesfeldt said, explaining that her colleague had put the two in touch. “We put our heads together and tried to figure out how we could carry his initial discoveries into clinical care.”

Soon after, the two conducted a study at the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center in Moshi, Tanzania, to see if NOHA can determine the estrogen receptor status in breast cancer patients. Miesfeldt said that the findings of this initial study were promising, and the NOHA blood marker had the potential to address cancer care.

“If we continue to prove that NOHA can replace costly standard estrogen receptor testing, now largely inaccessible in low resource settings … we’re opening the door to improve management of breast cancer patients in countries like Tanzania,” Miesfeldt said, noting that it would have the largest impact for health disparities in underserved populations globally.

Moving forward in the U.S., the team is examining the utility of NOHA in managing triple-negative breast cancer at multiple points during a patient’s treatment to identify if NOHA levels normalize as individuals respond to therapy through clinical trials at MaineHealth.

These studies are a crucial step in translating laboratory discoveries into clinical applications, Mohan explained, adding that they are also exploring the blood marker’s potential in the early detection of breast cancer for people with genetic predispositions and its role in drug development.

It lays the groundwork for more dynamic monitoring of cancer treatment effectiveness, Mohan said.

Normally, doctors can’t determine if a cancer regimen is effective until after the patient completes all planned cycles of chemotherapy, which can take up to six months. If the treatment is ineffective, the patient may have to start a new regimen, repeating the process.

With a blood test that tracks the NOHA biomarker, the physician could check NOHA levels after each cycle, and if the treatments show an unfavorable fluctuation, the physician can pause the specific drug combination and try a different one, Mohan said.

“We will be able to treat within those (initial) cycles, and it could have a much better outcome than going cycle after cycle or regimen after regimen,” he said.

The Vision of Advancement

Building on his initial breast cancer research, Mohan has expanded his work to include ovarian cancer.

According to the American Cancer Society, nearly 20,000 new cases of ovarian cancer are estimated to be diagnosed in the U.S. this year, with almost 13,000 women dying from the disease. Symptoms for ovarian cancer are generally less evident, if not absent, in the early stages and are often more noticeable as the cancer progresses.

His research showed that the NOHA biomarker could also be used to detect and monitor this type of cancer. This discovery led to a second patent covering the use of a blood diagnostic tool for identifying ovarian cancer.

“It validates to us that (NOHA) is not only going to be centric to breast cancer, but it can also expand to other tumors like ovarian cancer,” he said.

Throughout the expanding research initiative, Mahon has engaged over 30 UNE Doctor of Pharmacy students in focused research and scholarship related to the NOHA biomarker.

Experiences like these are significant, he said, because it helps future health care professionals tangibly understand the role of research in advancing medical knowledge and treatment options for patients. Most recently, Emmeline Graham, Pharm.D., a Class of 2024 graduate who is now a resident pharmacist at MaineHealth Maine Medical Center, worked with Mohan in his research.

“Working closely with Dr. Mohan in his lab has been an incredible experience,” Graham said. “As a future pharmacist, I wasn’t just learning about drug interactions and dosages in my program but given a chance to have a hand in the research that goes into developing new diagnostic tools.”

But engaging UNE students in the lab was only one side of the experiential educational equation. Miesfeldt currently has a UNE medical student participating in the clinical side of the research.

The student helped with clinical data validation, specifically looking at the chart and validating the clinical database that has been built as a result of the triple-negative breast cancer study.

Miesfeldt said, “We need to promote future researchers and future clinicians with a drive to make a lasting impact on patient outcomes.”

A sentiment echoed by Mohan.

“By involving (students) in research, we’re giving them a valuable perspective on how scientific inquiry can inform and improve patient care. This experience can make them better practitioners, more critical thinkers, and potentially collaborators in future clinical research,” he said.

The next steps of the collaboration between Mohan and Miesfeldt will involve scaling up the research for analytical and clinical validation of their findings, which is crucial for moving toward FDA approval and eventual commercialization of the NOHA biomarker test, Mohan said.

“This is where it is critical that we make the next transition to a commercializable product, to reach the people who would actually use it,” Mohan said. “This cancer detection tool has the potential to benefit individuals regardless of their economic status, in high-resource settings like the United States and in low-resource settings globally.”