UNE COM celebrates 40 years of being New England’s osteopathic medical school

Alumni, faculty, professional staff, founders, trustees, former trustees, clinical partners and other members of the University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine community will gather in Ripich Commons on the Biddeford Campus on June 29 for a celebration of the 40th anniversary of the completion of the college’s the first full year of classes. Commemorating UNE COM’s growth from the time it first ushered in its inaugural class of 36 students to the present, just weeks after the school graduated 178 new D.O.s., the occasion promises to produce fond memories of the past, moments of pride in how far it has come, and hopeful thoughts for the medical school’s future.

Though the event is technically being referred to as a “gala,” there will be something edging toward informality about the affair – and not informal in a generic way, with paper napkins and plastic party cups – but informal in a distinctly New England way that somehow combines a reserved sense of dignity with a flair for the casual. The celebration’s dress code, calling for “bow-ties and boat shoes,” perhaps says it all.

To those acquainted with UNE COM history, the ambiance will subtly acknowledge the college’s modest beginnings – beginnings, which, one could argue, are quintessentially “New England” in more ways than one. Certainly, the story of UNE COM’s creation is set in New England, the six-state region whose name the University bears; but the story is a New England tale in essence as well as place, emblematic of the long-standing New England cultural fabric that has been woven from dedication to hard work, self-sacrifice, regionalism, a sense of responsibility to community, and the preservation of self-autonomy.

The opening page of the UNE COM story book could easily be one graced with the illustration of an archetypal New England scene -- the handshake of neighbors over the fence separating their farms – for the activity depicted in this image was a seed from which UNE COM grew.

After the closure of the Massachusetts College of Osteopathy in the early 1940s, many years passed during which no osteopathic medical college existed in New England. As D.O.s in the region grew older, their anxiety increased. Who would replace them in retirement? Who would keep the osteopathic tradition alive in New England and treat the patients who had come to rely on osteopathic care? Surely, the necessity of traveling out of the region for their medical education did little to entice osteopathic medical students hailing from New England to return to their home states to practice and, likely, had the opposite effect.

As the 1970s approached, aging D.O.s in New England renewed their interest in the discussion of how best to continue the legacy of osteopathic medical education and osteopathic medical care in the area. They created the New England Foundation for Osteopathic Medicine (NEFOM) in 1973 and began exploring options for the creation of an osteopathic medical school on New England soil.

One of those concerned physicians was Bill Bergen, D.O., who happened to own a farm that bordered the farm of Jack Ketchum, then president of UNE’s precursor institution St. Francis College, which, at the time, was experiencing financial hardship. Talking over the fence one day, legend has it, the two men realized that they held the keys to a mutually beneficial relationship. As Dean of UNE COM Jane Carreiro, D.O. ’88, puts it, “Jack said, ‘Hey, Bill I’ve got some extra space and need more students.’ And Bill said, ‘Hey, Jack, we want to start a new medical school, and we need space.’” A practical Yankee swap if ever there was one.

With a solution to the issue of space, NEFOM still had to grapple with the very real problem of securing funding to get the school off the ground, and that proved to be a far more difficult obstacle than what could be remedied by a neighborly chat. But eventually, with donations raised by physicians throughout New England, including several who mortgaged their own homes to raise the money, the University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine opened its doors in 1978 with a faculty of 12.

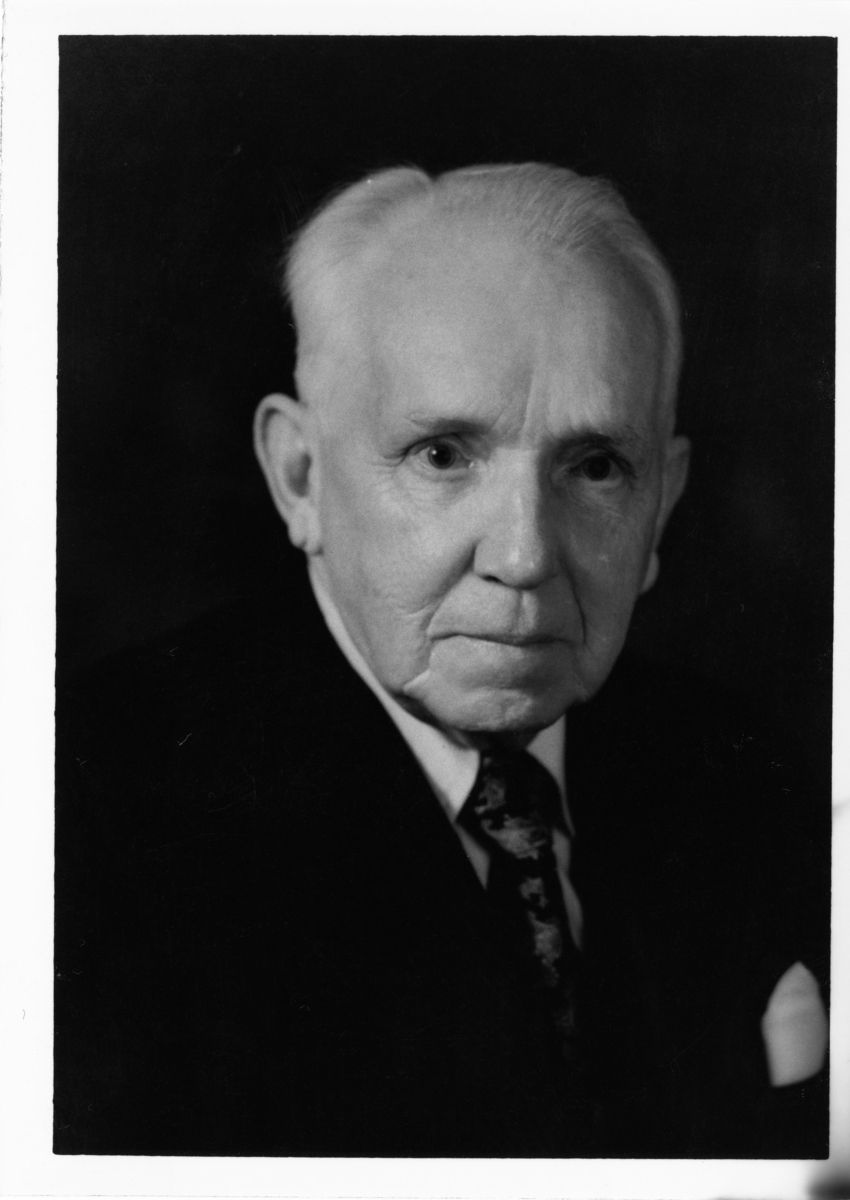

Some may interrupt our story here to ask why it was so important for a college of osteopathic medicine to exist in New England. After all, there were several universities in the region that graduated allopathic physicians. Surely, M.D.s graduating from Harvard and Yale, for example, were equipped to provide care to the New England population. But it was a different type of care whose legacy the founding members of NEFOM were interested in ensuring -- care that was based on the principles founded by Andrew Taylor Still, an American medical pioneer who conceived osteopathic medicine in the 1880s.

Some may interrupt our story here to ask why it was so important for a college of osteopathic medicine to exist in New England. After all, there were several universities in the region that graduated allopathic physicians. Surely, M.D.s graduating from Harvard and Yale, for example, were equipped to provide care to the New England population. But it was a different type of care whose legacy the founding members of NEFOM were interested in ensuring -- care that was based on the principles founded by Andrew Taylor Still, an American medical pioneer who conceived osteopathic medicine in the 1880s.

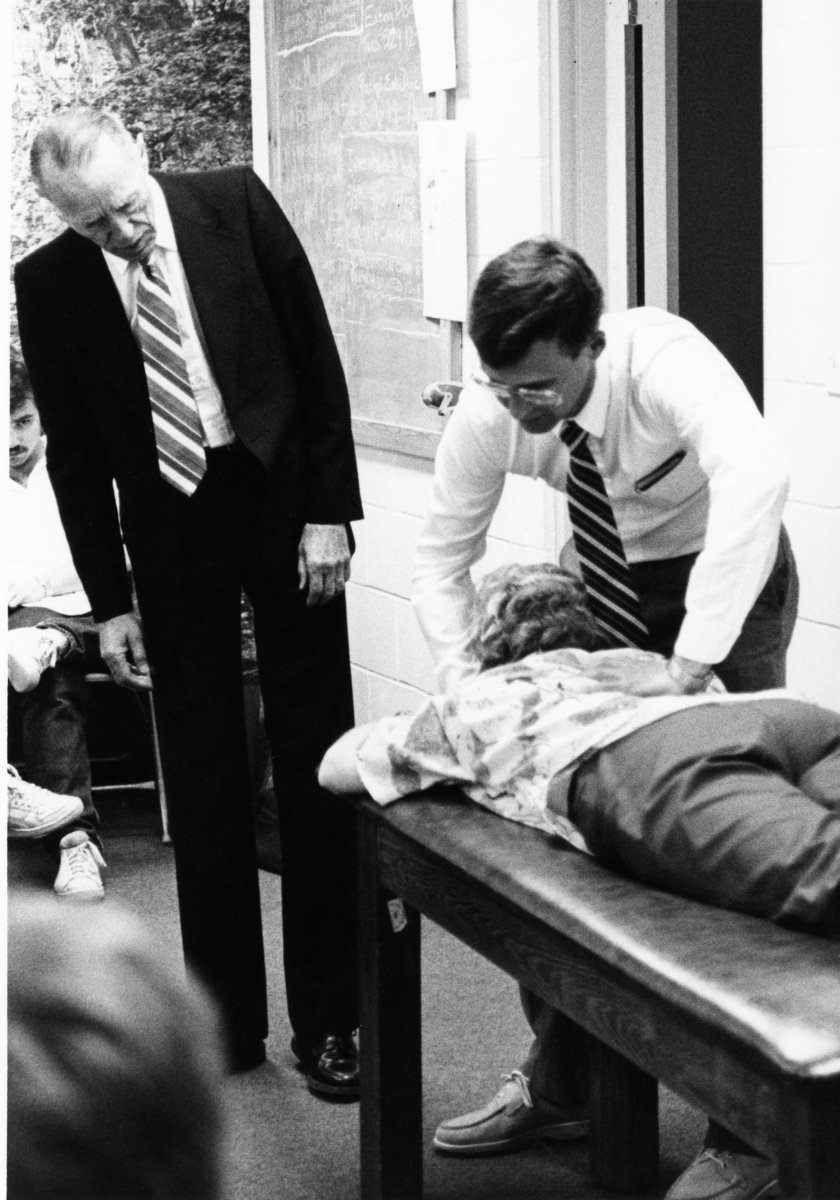

Regarding medicine as a marriage of science and art, Still’s philosophy called upon doctors to view the human body holistically as a well-integrated machine that functioned properly only when all systems and structures played in harmony. He rejected the notion that wellness could be achieved by diagnosing and addressing disease within a particular body part without examining and treating the patient as a whole human being. An important component of Still’s philosophy, and of osteopathy today, is the manipulation of the musculoskeletal system to aid the body is healing.

While the distinction between M.D.s and D.O.s is not as well defined as it once was in the mind of the general populace, there are key differences in approach that guide the way in which doctors in the two medical branches are trained. “Osteopathic medical schools tend to put a little bit more emphasis on generalist training,” Carreiro shares. “We want students to have a really strong generalist foundation. And philosophically, we tie that foundation to the idea of overall health. So, there’s a focus on ‘how do you keep somebody healthy?’ versus ‘how do you fix them when there’s something wrong?’ It doesn’t mean you can’t fix them, but the emphasis is put on health. The whole mind, body, spirit concept has been in osteopathy for 125 years. ‘Anybody can find disease,’ she says, quoting Still. “We want to promote overall health.”

While the distinction between M.D.s and D.O.s is not as well defined as it once was in the mind of the general populace, there are key differences in approach that guide the way in which doctors in the two medical branches are trained. “Osteopathic medical schools tend to put a little bit more emphasis on generalist training,” Carreiro shares. “We want students to have a really strong generalist foundation. And philosophically, we tie that foundation to the idea of overall health. So, there’s a focus on ‘how do you keep somebody healthy?’ versus ‘how do you fix them when there’s something wrong?’ It doesn’t mean you can’t fix them, but the emphasis is put on health. The whole mind, body, spirit concept has been in osteopathy for 125 years. ‘Anybody can find disease,’ she says, quoting Still. “We want to promote overall health.”

Long after Still established the first osteopathic medical school in Kirksville, Missouri, in 1892, osteopathy was still largely considered by mainstream medical providers as a “fringe” practice, some even deeming it a “cult.” Over the next 70 years, only four more colleges of osteopathic medicine were founded. But those who believed in osteopathic principles were ardent supporters and often felt, as did the many New England D.O.s who made personal sacrifices to establish UNE COM, that it was crucial for patients to be given the option of osteopathic care. Carreiro thinks that it was this selfless commitment to osteopathy – this “putting-your-money-where-your-mouth-is” attitude of UNE COM’s founders that is still at the heart of what makes the college so special. “They mortgaged their houses,” she says with a degree of bewilderment. “They really put it out there. They put skin in the game. And I think that, for many of us, the fact that somebody did that and took those chances so we could be here and have the careers we have – we all sort of feel like we owe it to them.”

The whole mind, body, spirit concept has been in osteopathy for 125 years. Anybody can find disease; we want to promote overall health.” -- UNE COM Dean Jane Carreiro, D.O. '88

Patricia Kelley, M.S., associate dean of Recruitment, Student, and Alumni Services for UNE COM, agrees that the concept of repayment is ingrained in the students. Without a teaching hospital, UNE has always relied on community physicians, some traveling long distances, to teach students. “It was their way of giving back and contributing,” explains Kelley. “And so students just automatically said, ‘Well, that’s what I need to do when I reach a certain point in my career.’ And so even today, we still have people coming back and saying, 'You know, it’s my turn to pay it back. I want to get involved in being in the classroom,’ and the ethos just continues. You see it out in the rotation sites, you see it when they want to come back and mentor the students or when they recommend that students apply here based on their own experiences. It’s just part of our DNA.’”

Patricia Kelley, M.S., associate dean of Recruitment, Student, and Alumni Services for UNE COM, agrees that the concept of repayment is ingrained in the students. Without a teaching hospital, UNE has always relied on community physicians, some traveling long distances, to teach students. “It was their way of giving back and contributing,” explains Kelley. “And so students just automatically said, ‘Well, that’s what I need to do when I reach a certain point in my career.’ And so even today, we still have people coming back and saying, 'You know, it’s my turn to pay it back. I want to get involved in being in the classroom,’ and the ethos just continues. You see it out in the rotation sites, you see it when they want to come back and mentor the students or when they recommend that students apply here based on their own experiences. It’s just part of our DNA.’”

The DNA is clearly a recipe for success. UNE COM was among the first colleges of osteopathic medicine to receive Accreditation with Exceptional Outcome, the highest level of accreditation a D.O. school can receive. Having graduated more than 3,700 doctors over the past 40 years, the college is the number one provider of physicians for the state of Maine and the number one provider of D.O.s for New England. Of course, UNE COM has undergone substantial change through the decades – evolutions that have been both contributors and responses to this enormous growth.

They mortgaged their houses. They really put it out there. They put skin in the game. And I think that, for many of us, the fact that somebody did that and took those chances so we could be here and have the careers we have – we all sort of feel like we owe it to them.” -- UNE COM Dean Jane Carreiro, D.O. '88

The third-year experience, for example, is very different from how it used to be. Kelley remembers a time when third-year students completed four-week rotations, which they themselves were responsible for securing. “They would go up and down the eastern seaboard and as far west as the Mississippi, and pretty much they had to find their places … like lone soldiers,” she remarks.

The third-year experience, for example, is very different from how it used to be. Kelley remembers a time when third-year students completed four-week rotations, which they themselves were responsible for securing. “They would go up and down the eastern seaboard and as far west as the Mississippi, and pretty much they had to find their places … like lone soldiers,” she remarks.

Kathryn Brandt, D.O. ’97, M.S. ’11, Med.L., associate clinical professor and chair of UNE COM’s Department of Primary Care, remembers those days as a student. “We used to bump into each other on the freeway because every four weeks, we were all going up and down I-95,” she reminisces. Today, with 17 clinical campuses, UNE COM is able to place each third-year student in a designated spot at facilities with which the college interfaces on a regular basis. The result is a more standardized curriculum and well-rounded exposure to different medical settings for all students. “It’s like we have 17 different campuses,” says Carreiro with a gleam of pride.

The ethos just continues. You see it out in the rotation sites, you see it when they want to come back and mentor the students or when they recommend that students apply here based on their own experiences. It’s just part of our DNA.’” -- Pat Kelley, M.S., associate dean of Recruitment, Student, and Alumni Services

Other changes include more course integration, clerkships that have increased from one-and-a-half years to two years, and a greater emphasis on team learning and team teaching. Brandt recalls, “When I was in school, you could be in lectures for the whole day, and now, the lectures are a very minimal part of it. It’s very interactive, and there’s an enormous amount of small group learning, team learning, and teacher learning. It’s not just about what you know. It’s about how you interact with folks and how you think things through. How you function in a team becomes a large part of how you’re assessed.”

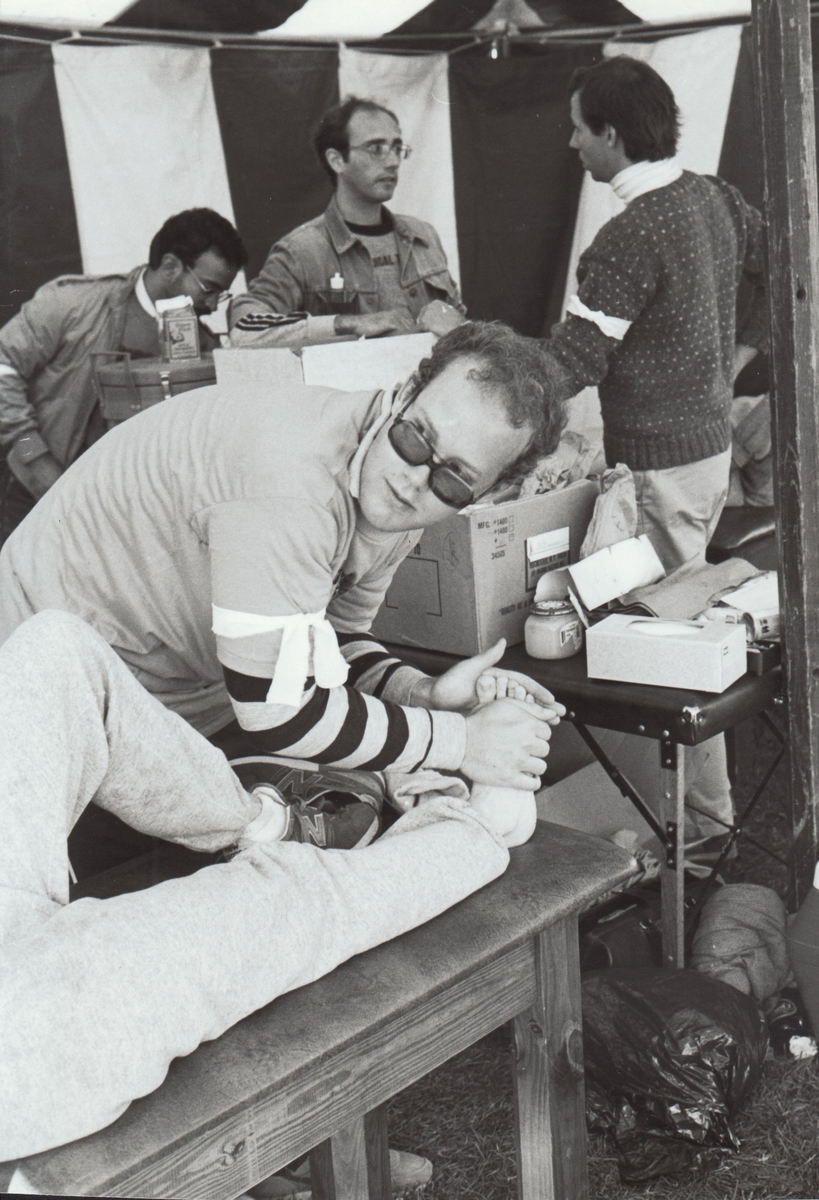

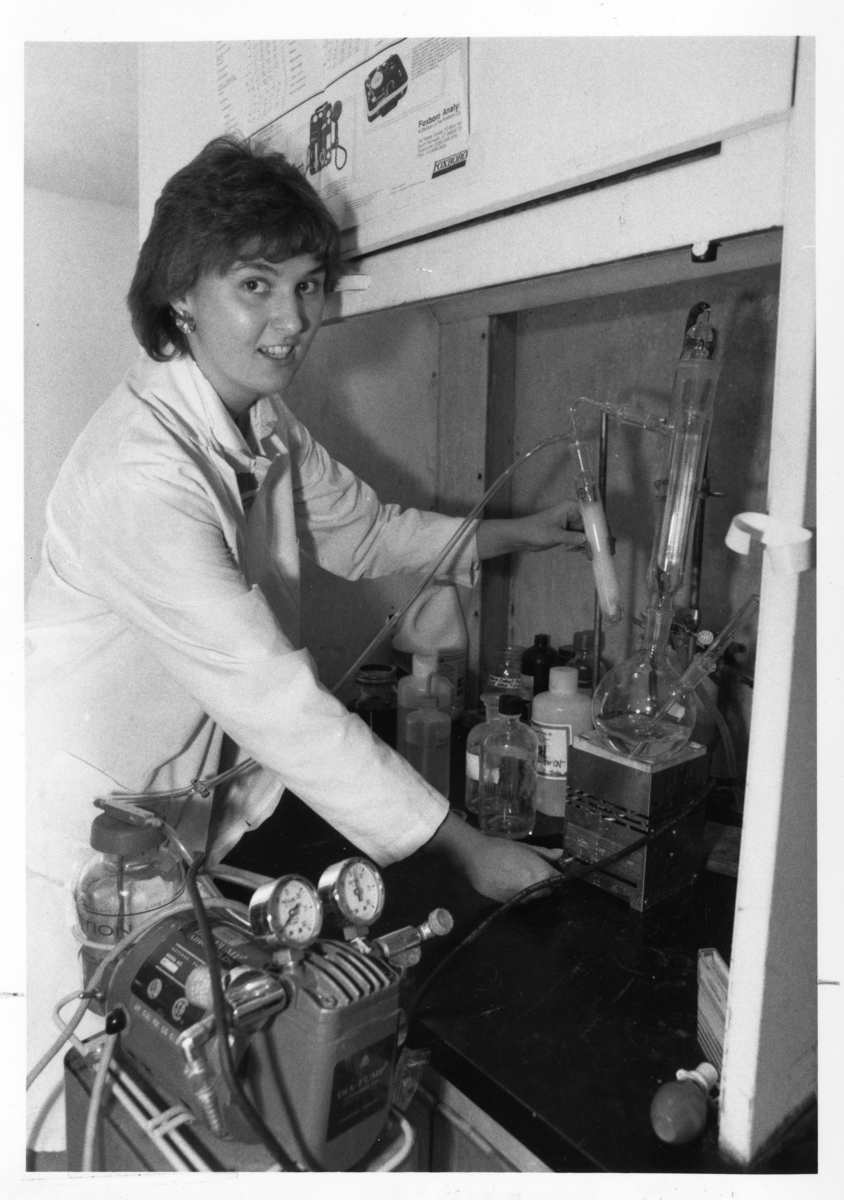

This emphasis on teamwork is at the heart of interprofessional education (IPE) – a movement in health care training of which UNE has been at the forefront. UNE COM’s focus on holistic health care is a significant driver in UNE’s overall expertise in interprofessional education across the University. One hundred percent of UNE COM students engage in IPE and IPP (interprofessional practice) during their clerkships.

Of course IPE/IPP is a natural fit with osteopathic medical training, given osteopathy’s focus on the comprehensive integration of all facets of health. But Carreiro views the unique character of UNE COM itself also as representative of this holistic philosophy. She elaborates: “I think one of the reasons the students and our graduates feel such a connection to the school and to everybody in the school is because, looking at this web of how everything is connected, it’s not just about getting students through their courses so they can graduate; it’s about helping students find what their passions are through clubs and organizations; it’s supporting them; it’s making sure they find the mentors they need to find. It goes back to the osteopathic philosophy of being respectful of whatever the conditions are that are needed to allow an individual to express their health; for some that’s “Health” with a capital “H,” but for many people, that’s their success.”

Of course IPE/IPP is a natural fit with osteopathic medical training, given osteopathy’s focus on the comprehensive integration of all facets of health. But Carreiro views the unique character of UNE COM itself also as representative of this holistic philosophy. She elaborates: “I think one of the reasons the students and our graduates feel such a connection to the school and to everybody in the school is because, looking at this web of how everything is connected, it’s not just about getting students through their courses so they can graduate; it’s about helping students find what their passions are through clubs and organizations; it’s supporting them; it’s making sure they find the mentors they need to find. It goes back to the osteopathic philosophy of being respectful of whatever the conditions are that are needed to allow an individual to express their health; for some that’s “Health” with a capital “H,” but for many people, that’s their success.”

The impact that UNE COM has had over the past 40 years is extensive and multifold. Perhaps most importantly, the college’s 3,700 graduates have provided choice, education and health empowerment to countless patients throughout the region, across the nation and around the world. Between direct patient care and the college’s impressive contributions to biomedical and clinical research, particularly in areas of pain, healthy aging, and disease, the number of people whose lives have been touched, directly or indirectly, by UNE COM graduates and faculty is undoubtedly staggering.

We used to bump into each other on the freeway because every four weeks, we were all going up and down I-95 -- Kat Brandt, D.O. '97, M.S. '11, Med.L., associate clinical professor and chair of Primary Care

UNE COM’s impact just in Maine alone is beyond impressive. Much of the reason why we’re the top provider in the Maine health system is because we send students into these in-state rotations in their third-year,” explains Carreiro. “They get the exposure, and they want to come back after residency to practice.”

UNE COM’s impact just in Maine alone is beyond impressive. Much of the reason why we’re the top provider in the Maine health system is because we send students into these in-state rotations in their third-year,” explains Carreiro. “They get the exposure, and they want to come back after residency to practice.”

The college has been a boon to Maine financially as well, with 1,650 primary care jobs filled by UNE COM alumni that collectively boast a $100 million economic impact on the state.

In keeping with the osteopathic principles that focus on holistic healing, D.O.s gravitate toward primary care, and UNE COM is no exception. In fact, 61 percent of UNE COM alumni in Maine practice in primary care, which is especially important in rural and underserved areas, where specialists are few, and primary care physicians are relied upon heavily. In fact, UNE COM has achieved immense success in providing physicians to official Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) within the state. Since 2008, the college has seen a 32 percent increase in the number of graduates practicing in HPSAs, with 40 percent of graduates who are practicing in Maine doing so in rural and underserved areas. This is no coincidence, says Kelley. She notes of UNE COM students, “We expose them early and often to rural settings.”

“It’s a little bit of the ‘Which came first, the chicken or the egg?’ scenario,” she muses. “I’ve been asked, ‘Do you just attract the type of student who wants these [rural] experiences?’ I think for us, it’s providing an opportunity. If this is something that you want to be exposed to, then you can get that here. This is something that we can offer that other schools may not be in a position to offer.” She points to the Care for the Underserved Pathways (CUP) Scholars Program offered by UNE’s Center for Excellence in Health Innovation, the Maine Area Health Education Center (AHEC) Network and participating programs at UNE. With the objective of increasing the number of health professions students who practice in rural and underserved communities upon graduation, the CUP Scholars Program provides a rural health immersion opportunity for health professions students to increase leadership skills, gain competencies in interprofessional education and team-based practice, and understand and address health disparities and the social determinants of health in rural and underserved communities.

Full participation in the Doctors for Maine’s Future Scholarship Program is another means through which UNE COM does its part to alleviate Maine’s shortage of physicians. Doctors for Maine’s Future encourages medical students from Maine to stay in state after graduation by mitigating the cost of medical school. “It’s an opportunity for students in Maine to be able to get an education and pursue the type of medicine that they want to pursue as opposed to being constrained by debt,” states Kelley. “Rather than going into the highest-paying specialty so they can pay their loans back or going out of state to make more money, students who want to go into primary care can go into primary care. Those who want to pursue a specialty can do so in their home state.” A condition of accepting the scholarship is an agreement to perform all third-year clinical rotations in Maine.

Full participation in the Doctors for Maine’s Future Scholarship Program is another means through which UNE COM does its part to alleviate Maine’s shortage of physicians. Doctors for Maine’s Future encourages medical students from Maine to stay in state after graduation by mitigating the cost of medical school. “It’s an opportunity for students in Maine to be able to get an education and pursue the type of medicine that they want to pursue as opposed to being constrained by debt,” states Kelley. “Rather than going into the highest-paying specialty so they can pay their loans back or going out of state to make more money, students who want to go into primary care can go into primary care. Those who want to pursue a specialty can do so in their home state.” A condition of accepting the scholarship is an agreement to perform all third-year clinical rotations in Maine.

It’s an opportunity for students in Maine to be able to get an education and pursue the type of medicine that they want to pursue as opposed to being constrained by debt,” -- Pat Kelley, M.S., associate dean of Recruitment, Student, and Alumni Services

An important component of the program is that scholarship money from the state must be matched by UNE COM through private philanthropy, and since the program’s inception in 2009, UNE COM has received the maximum amount of matching funds from the state of Maine, providing 58 UNE COM students with scholarships. As members of the UNE COM community look forward to the next 40 years, they can be assured that the generosity and spirit of “paying it forward” demonstrated by UNE COM’s founders is alive and well.

The future of osteopathy in the U.S. is a bright one. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, 25 percent of today’s students who are entering medical school are enrolling in osteopathic programs. By comparison, only seven percent of today’s practicing physicians are D.O.s. It is only a matter of time before the percentage of the nation’s physicians that D.O.s constitute will leap significantly.

UNE COM’s role in this rapid national growth of osteopathy cannot be overstated, and Kelley says that this is in part the result of UNE COM graduates taking on significant roles in the educational sphere. Four alumni are current deans of osteopathic medical schools; another alum is the outgoing president of the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine; and a number of department chairs at osteopathic schools across the country got their D.O. degrees from UNE COM. “I’m constantly amazed at the breadth and the influence that people coming out of this tiny, little podunk school have had on the education of the next generation of students,” remarks Kelley with a chuckle.

UNE COM’s role in this rapid national growth of osteopathy cannot be overstated, and Kelley says that this is in part the result of UNE COM graduates taking on significant roles in the educational sphere. Four alumni are current deans of osteopathic medical schools; another alum is the outgoing president of the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine; and a number of department chairs at osteopathic schools across the country got their D.O. degrees from UNE COM. “I’m constantly amazed at the breadth and the influence that people coming out of this tiny, little podunk school have had on the education of the next generation of students,” remarks Kelley with a chuckle.

What may not be as obvious as UNE COM’s far-reaching impact is that the college has attained success, not despite its location but, rather, to some extent, because of it. Carreiro expounds on one interpretation of that conclusion: “We are really on the cutting edge. We really seem to be always pushing the envelope. And I think part of that is because we're in the northeast and, for many, many years we, as a medical college, have been exposed to and have been competing with and vying for applicants with the other medical schools in the northeast. So we have had to learn how to walk like them, talk like them, think like them -- but still be us.”

And being “us” means that even at the 40th Anniversary Gala, wearing boat shoes is not only acceptable; it’s encouraged. Being “us” means that in some small way, we intrinsically understand that adding that touch of “New England casual” to our gala ensembles gives a nod to osteopathy’s rural roots; it acknowledges the sacrifice that New England D.O.s made when they pulled together, despite great risk to their own financial welfare, to secure osteopathic choice for the region they called home, and it reminds us that good neighbors and a firm handshake can go a long way up here.

And, perhaps most importantly, it demonstrates that we understand just what Dean Carreiro means when she sums up the college’s future by stating, “I think we’re in a really good place.”