Responsible Grounds Maintenance

In addition to UNE’s 187 acres of land that have been preserved as conservation area, the University owns 136 acres of developed land. As with any university campus, much of the developed land includes flower beds, grass lawns, and athletic fields. UNE’s grounds crew seeks to maintain exemplary aesthetics that includes texture, color and diversity and strive to balance the University community’s desire for organic practices with the demands of maintaining the campuses’ beauty. This is accomplished by a “think first, spray last” philosophy, consistent with the Maine Board of Pesticide Control and coupled with preventative efforts where pest and fertilizer needs exist. There is also growing interest and recognition of the attractiveness of perennial and native plants.

Additionally, themed gardens have been increasing on campus and connect the land to curricular areas as diverse as environmental science, pharmacology, art, and agriculture. All of these projects have benefited from collaboration between faculty, who have joined forces across curricular areas to offer research and multidisciplinary support; staff, including Facilities, Library, and Sustainability employees who have provided labor, funding, and advocacy support; and students, who have been integral to project success through internships and funding advocacy.

We invite you to explore each of these gardens and projects and join the effort.

Integrated Pest Management

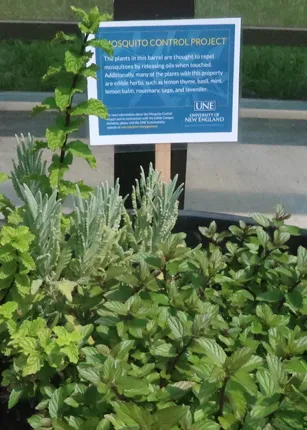

Mosquito Control Project

Our Biddeford Campus, located in beautiful coastal Maine on 560 acres, is situated at the mouth of the Saco River where it flows into the Atlantic Ocean. Habitats including forested vernal pools, marshes, and wetlands create ideal locations for mosquitoes and their resulting mosquito-borne viruses. The goals of the University’s Integrated Pest Management (IPM) Program include maintaining a safe and sustainable campus environment and protecting human health by suppressing pests that threaten public health and safety. A natural predator approach is a logical solution.

The mosquito control project, originating from a collaborative effort between the Environmental Health and Safety Department and environmental programs, has been the backbone of the biological control approach to reducing mosquito populations at the Biddeford Campus. This component of the IPM program involves creating a habitat for mosquito-eating birds and bats and increasing the presence of mosquito-repellent plants. The two departments collaborate to oversee the education and work of student interns who manage the program each summer.

Birds

There are 20–35 birdhouses in any given year on UNE’s Biddeford Campus. These boxes were designed to host nesting native Eastern bluebirds and tree swallows. Because mosquitoes are one of their food sources, the birds provide a natural way to reduce mosquito populations.

Each summer a student intern closely monitors each birdhouse, checking for nests, eggs, and young. The students get to know each clutch of baby birds personally as they hatch, and they weigh and leg-band the chicks for record-keeping purposes. We also band adult birds that return to their nesting places to mate and raise their clutch of eggs each year. We collect fecal samples from the adults and chicks and use molecular techniques to identify what species of mosquitoes the adults eat and feed their chicks, if they eat different species in different times of the summer, and if bluebirds and tree swallows differ in their use of mosquitoes as food.

IPM Plants

Naturally mosquito-repellent plants, such as lavender, basil, rosemary, marigolds, and — most importantly — Citrosa, or scented geraniums, are favored alternatives to synthetic mosquito-repellent chemicals. An important component of the mosquito control project on the Biddeford Campus is the strategic placement of potted plants at the entrances of most buildings.

The key to activating the fragrances that keep mosquitos away is to physically brush and rub the leaves of all these plants. Our Grounds Department discovered a clever way to encourage this behavior is to plant more edibles, including cherry tomatoes, in the pots. When people pass the pots and reach in to pick a tomato or herb, they inadvertently brush the leaves of the mosquito-repellent plants, releasing the beneficial fragrances.

Bats

Bats eat various bugs, such as night-flying insects, flies, mosquitoes, moths, and beetles. A little brown bat can eat up to 1,000 mosquitoes an hour. Several bat boxes have been placed on campus to provide much-needed habitat, but to date, few have used them in the summer months.

Providing homes for the eight different bat species in Maine is more crucial than ever. White Nose Syndrome — Geomyces destructans — caused the bat population to decline by 90% in hibernacula across New England. White Nose Syndrome causes the bats to wake from their winter hibernation prematurely and use the fat reserves they have stored to make it through the winter.

Garden Projects

Rain Garden

Rain Gardens are a form of low-impact, sustainable landscaping, intended to mitigate the effects of rainfall on impervious surfaces, such as pavement and rooftops. Situated at the source of stormwater run-off, a rain garden is designed to slow the flow of water, absorb excess nutrients, and filter pollutants.

In 2013, 49 students and five faculty members came together, as part of a collaborative environmental service-learning project (funded by an EPA subgrant through Maine Campus Compact) to plan and create a rain garden in the Marcil/Morgane parking lot on UNE’s Biddeford Campus.

The students collected an annotated bibliography about rain garden design and case studies of other campus projects, developed design, installation, and maintenance plans for the garden, grew the majority of plants from seed, planted the garden, and developed educational materials for use in the garden. Tremendous collaborative support was lent by the Facilities team during construction.

UNE’s rain garden collects stormwater from the surrounding parking lots and inflow pipe, as well as direct rainfall. The 150+ plants in the rain garden, representing 17+ species, were specifically chosen for their ability to tolerate drought and/or excess water conditions. All of the plants in the rain garden are native to Maine, providing valuable resources and habitat to Maine’s native wildlife.

Multiple plant characteristics were accounted for in the design of the garden for aesthetic and practical purposes. Plant height, texture, bloom color, bloom season, water, and soil requirements were all features that played into the arrangement of plants. Moreover, the garden’s aesthetics were enhanced through the addition of a stone walking path, wooden signage and a bridge (made of wood sourced from a local business), and seating (made from 240 recycled milk jugs).

The rain garden continues to serve as a natural laboratory for UNE researchers and science and environmental studies classes, while also benefiting the community as a whole.

Native Prairie Garden

In the spring of 2013, students taking an Environmental Studies course in ecological restoration planted a native prairie garden in the parking area near the Student Academic Success Center on UNE’s Biddeford Campus. Composed of wildflower and grass species native to Maine, the garden’s plants were grown from seeds by the students.

While typical lawn and backyard landscaping involves non-native grasses and flowers that require significant inputs of water, chemicals, and fertilizers, as well as frequent use of polluting equipment to maintain the desired appearance, the native prairie garden reduces the energy and resources needed to maintain landscaping. Well-adapted to Maine’s climate, these plants are deep-rooted, hardy, and non-invasive, and they serve as host-plants required by native butterflies and other vital insect species. They demonstrate how human-modified landscapes can be beautiful while contributing to biodiversity and a healthier ecosystem.